Shimmer is a gem, and I don’t say that solely because they’ve given a home to two of my disheveled little pieces. Shimmer finds itself home to a lot of beautiful strays. It’s a speculative fiction magazine that has carved a place for itself for bedraggled bits of wonder, lovingly polished and arranged. I’m proud to be a part of it, especially this, its latest incarnation.

In the introduction to issue #27, the editor writes that all the included pieces all fit together if viewed from the right angle. (She says something like that.) They’re like interlocking puzzle pieces, but you have to cock your head just right to see how the combined scene flows. I like that, because it’s just true enough. You’ll come away from these stories knowing how they fit together, and I’ll come away knowing the same thing. But we’ll probably know differently.

To me, besides the gilded edges of wonder common to whatever Shimmer publishes, what held these stories together was a sense of loss. An ache. Something departed.

We start with Alix E. Harrow’s piece, “Dustbaby.”

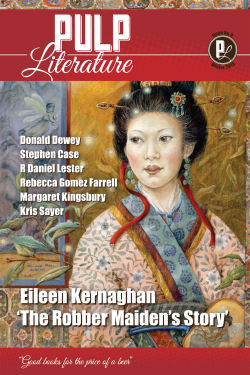

No, we don’t. We start with the cover. Judge this magazine by its cover. The watercolors that Sandro Castelli does for each issue are one big detail that holds Shimmer together and makes it work. They’re lovely and lend a haunting consistency to the magazine’s shelf-appeal.

Now, start with Alix E. Harrow’s piece, “Dustbaby.” I don’t think I’d go so far as to call it an end-of-the-world story, because it’s not among those pieces of ecological devastation or infection or whatever that I’m getting tired of reading. It’s a bit deeper than that, and by that I mean historically richer. We’re back in the Dust Bowl, reimagined. What if the Dust Bowl had been the end, the casting off of a thin crust of tired soil so that something greener and wetter underneath could reemerge? What haunted those hills before our plows passed?

Harrow, herself a historian, does good work here. The images are rich, moving, and disturbing, and we get a reminder that some of the best stories don’t have endings but rather just larger beginnings—part of what’s so much fun about short stories.

(If you like magical apocalypses like “Dustbaby,” you might check out my own “The Crow’s Word,” published in Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show.)

My favorite piece in this issue (and yes, I might even be including my own) was K. L. Owens’ “A July Story.” Who doesn’t love a haunted house? And who doesn’t love a house with a mind, a mute tongue, and rooms stretching backward and forward in space and time? It might sound too much like the plot of an episode of Doctor Who, if “A July Story” wasn’t so steeped in character and place.

What makes this story work so well, beyond simply a compelling idea, are the characters: Kitten and Lana, and the place: the Pacific Northwest. Kitten’s a child of the English Industrial Revolution, torn out of time, marooned everywhere and nowhere. Lana’s a young girl from today. Their encounter, dialogue, and ultimate trajectories make a haunted house story a lot more than you expect. It’s also an especially strong tale because it takes place on a deeply textured backdrop of a particular time and space, which Owens makes clear in the interview following. Highly recommended.

Then you get to read my story, which is called “Black Planet.” I explained about this a bit in my interview in the issue (which you only get if you purchase the entire issue), so I won’t repeat that here. But I really like this little piece; I think it’s among the best I’ve written, and it’s for my sister.

The final piece in this work is the shortest, “The Law of the Conservation of Hair,” by Rachel K. Jones, which reads like a prose poem (and in fact might be in actuality a prose poem) about love and alien invasion and loss. Read it at least twice. Favorite line: “That we will take turns being the rock or the slingshot, so we may fling each other into adventure.”

So what about the common theme? Things get lost in different ways. Land, lives, siblings, and loves. Why do we sometimes feel richer for the loss—or rather, for the expression of the loss?

Do yourself a favor and grab Shimmer #27.